Introduction

Earlier this year, BERL hosted focus groups as part of our green pro bono study. This Community Climate Action series shares the common themes that were discussed at these focus groups. The focus groups followed on from our Regenerative, distributive, resilient Aotearoa discussion document that was published last year; the discussion document provided a starting point for kōrero at the focus groups.

The discussion document asked: ‘What does a low-emission, regenerative, distributive, and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand look like for communities?’. The document provided BERL’s perspective of the economy and its role in achieving this vision for Aotearoa New Zealand. The key premise of this article was that a wider economic model that values our people and our planet is valid and necessary. Not only is it valid and necessary, it is fundamental if Aotearoa New Zealand is to overcome our twenty-first century challenges.

Once the discussion document was published, we invited a range of people to attend our focus groups. The purpose of the focus groups was to engage with others involved in the climate and ecological space, encourage participation in this kōrero from varying perspectives, share knowledge, learn from each other and to work together towards our shared objective of a healthy planet. We were extremely privileged to have a range of attendees that are passionate about community climate action. These attendees represented various community-led initiatives, and included people from the community sector, environmental organisations, sustainable businesses, academia, and more.

This Community Climate Action series shares the common themes, and the related insights, that were discussed at these focus groups. Accordingly, this series will explore:

- Systems change – provides an overview of the theory of systems change, and explains the focus group attendees’ comments

- Power sharing – explores power sharing between Māori and the Crown, central government and local government, and the government and communities.

- Value of community organisations – discusses the value of community organisations, and their contribution to community wellbeing

- Realising community organisations’ potential – details how community organisations can realise their potential through greater funding and resources.

We would like to thank all those who were involved; we greatly appreciate your contributions and feel incredibly privileged that we could connect with you on this kaupapa.

Systems change

A common theme among the focus groups was the need for systems change. Terms such as mind-set shift, leverage points, systems approach, behaviour change etc. were used when discussing combating climate and ecological breakdown. But what exactly is meant by systems change and how are community organisations using it for climate action?

The twin environmental and social crisis that the globe faces are complex and interconnected challenges that require systemic solutions.

“The world is a complex, interconnected, finite, ecological-social-psychological-economic system. We treat it as if it were not, as if it were divisible, separable, simple, and infinite. Our persistent, intractable, global problems arise directly from this mismatch” (Meadows, 2010).

Systems change is a systematic approach to addressing the root causes of social and environmental problems. Systems change is both a verb and a noun; it is both a process and an outcome. One definition of systems change as a process is “a transition that is a radical, structural change of a societal (sub)system that is the result of a co-evolution of economic, cultural, technological, ecological and institutional developments at different scale-levels” (Rotmans et al, 2001). Systems change as an outcome has been defined as “the emergence of a new pattern of organisation or system structure. That pattern being the physical structure, the flows and relationships or the mind-sets or paradigms of a system, it is also a pattern that results in new goals of the system” (Birney, 2015).

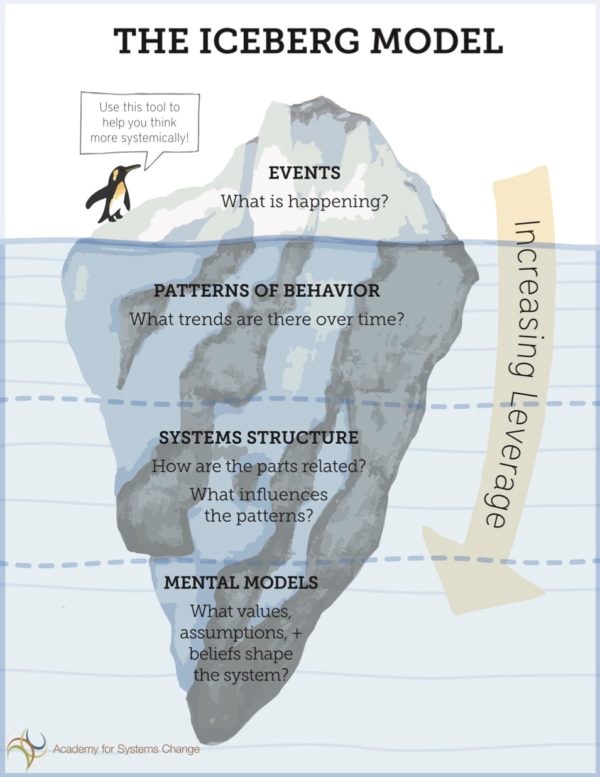

Systems change is widely used for climate action. The field of systems change encompasses a wide range of techniques, methodologies and approaches. A framework that is widely used is the Iceberg Model (shown in Figure 1). This tool is designed to help discover the patterns of behaviour, supporting structures, and mental models that underlie a particular event. The Iceberg Model enables us to look beyond the immediate events to uncover the root cause of why that event was happening. The Iceberg Model highlights that mental models are at the root of an event, and that changing mind-sets can have the most leverage for creating change. Mind-sets include both individual and collective mind-sets.

Figure 1 The Iceberg Model

Source: Academy for Systems Change

The focus group attendees also felt that mind-set shift was fundamental for climate action; mind-set shift was mentioned in every focus group. One attendee is involved in a community organisation in the zero-waste space that used a systems change framework that was adapted from Abson et al (2016) to create systems change by shifting to a circular economy. This framework outlined that the most effective levers to pull for change are activities and infrastructure, processes and flows, regulatory framework, and mind-set. These levers are listed in order of increasing importance. Furthermore, mind-set shift is considered the most effective lever. The attendee that uses this framework reflected this in the focus group, they stated that “mind-set is the hardest to shift, but it is the most effective lever”.

Another attendee mentioned that a guiding principle for systems change is seeing connections, rather than taking a siloed approach. This approach was evident by other attendees who discussed the environmental and social crisis as interconnected, and advocated for climate action that is intertwined with social justice. Furthermore, climate change mitigation does not inherently create social justice or climate justice. However, there are growing calls for climate change mitigation to be just and equitable. One example of an attendee approaching climate action through social justice was in the energy sector. The attendee questioned the objective of climate action; is it solely for climate, or also for equity? This is important because climate action will be different based on the objective. The attendee explained that hardship and climate change are very different drivers. This attendee pointed out that renewable energy may be good for the environment, but that energy also needed to be decentralised to create equitable outcomes. Overall, the focus groups attendees approached climate action through an equity lens.

Another attendee expressed that we are constantly dealing with the symptoms of the environmental and social crises, rather than addressing root causes. The attendee corrected our ‘burning platforms from an economic perspective’ (see Figure 1 in the discussion document) by placing racism and colonialism at the foundation of the burning platforms. This was on the basis that racism and colonialism underpin all issues. If New Zealand is going to combat the climate and ecological crisis, then it needs to face up to dealing with the root causes, rather than the symptoms. A potential first step for creating systems change by dealing with the root causes is power sharing. This is the topic of the next chapter in this series.

Power sharing

New Zealand’s transition to a low-emissions economy is about power as “transitions are inherently political processes”, and “politics is inextricably linked with the notion of power” (Geels et al, 2019). As such, power is central to climate action. A common discussion in the focus groups was regarding the role that power plays in climate action. Discussions included the idea of power sharing between Māori and the Crown, central government and local government, and the government and communities.

In the New Zealand context, power sharing with Māori is central to questions of power. As such, power sharing with Māori is central to climate action. However, as some focus group attendees noted, mainstream environmental groups are not ethnically diverse, and do not adequately address environmental issues faced by Māori. Pākehā working in the climate and ecological space should be asking ‘how can we, as allies, be actively committed to Te Tiriti?’ or posed differently, ‘how can we be Tangata Tiriti (Treaty People)?’ Advocating for tino rangatiratanga, decolonisation, and constitutional transformation may be an approach. These were all discussed in the focus groups. This chapter explores these interconnected ideas in the hope of raising awareness.

Article two of Te Tiriti promised chiefs tino rangatiratanga (total chieftainship or sovereignty) over their whenua (land), kāinga (villages), and taonga (treasures). This promise has not been upheld, however. Tino rangatiratanga involves power sharing between Māori and the Crown. Our discussion document stated that honouring Te Tiriti so that Māori have tino rangatiratanga must be the foundation from which Aotearoa New Zealand combats climate and ecological breakdown. Tino rangatiratanga as a requirement for climate action is also likely to create more just and equitable outcomes. One of our attendee advocates that climate justice equals indigenous justice.

The importance of decolonisation was also discussed. Decolonisation is the idea that power imbalances are addressed and that the ideas, knowleges and value sets that underpin the systems that shape Aotearoa New Zealand reflect Te Ao Māori and Te Ao Pākehā (see here for further explanation of decolonisation). One attendee stated that transferring power involves acknowledging that Māori may just want to do by Māori for Māori in Māori ways. This attendee highlighted that relationships need to be strong to recognise that. A way to strengthen relationships could be through constitutional transformation.

Constitutional transformation was mentioned in each focus group at least once. Within minutes of the first focus group, Jacinta Ruru and Jacobi Kohu-Morris’s Spinoff article was endorsed by an attendee. This article imagined an alternative to New Zealand’s constitutional framework in a way that gives Te Tiriti o Waitangi the mana it deserves and Māori a meaningful seat at the table. In other focus groups, the Matike Mai Aotearoa report was explicitly discussed. The Matike Mai report was created by the Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation. It describes a different type of constitutionalism that is based upon He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti rather than “how the Treaty might fit within the current Westminster constitutional system” (Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation, 2016). The report outlines six indicative constitutional models. These models provide a visualisation for reimagining governance. A founding kaupapa for the models was constitutionally reconceptualising kāwanatanga (the Crown) into its own sphere of influence, distinct from the rangatiratanga sphere. The kāwanatanga sphere would still be rooted in the history of Westminster sovereignty but it would not be a dominating power that is unchallengeable. Instead, the Crown would exercise “a more honourable power that prizes relationships”. Constitutional transformation is a way to rebalance power in Aotearoa New Zealand.

An attendee expressed that addressing the climate and ecological breakdown requires the redistribution of power. Power sharing with Māori is central, however it is also includes power sharing with communities in general. Furthermore, another attendee stated that there needs to be a transfer of power back to communities. Firstly, this could involve power sharing and redistributing resources to local council. Under the leadership of the current Government, central government is expanding and is trending towards centralisation, while local councils are struggling. This highly centralised government is not sharing the power. This limits community self-determination. Increased power sharing between central government and local government was presented as an opportunity for climate action.

It was also argued that transferring power back to communities from government (central and local) was necessary to support community climate action. An example of how to share power with communities is distributed and decentralised systems. This means that activities, particularly those regarding planning and decision making, are distributed away from a central, authoritative group. Distributed and decentralised was discussed in relation to energy and food. For example, community smart grids for peer to peer electricity trading enables renewable energy generation, distribution, trading, and management of energy locally. Decentralised food networks, such as urban agriculture and community gardens, were also discussed. Decentralisation can give a person power over their energy and food. It has been recognised that we cannot transition to a low-emissions economy unless it is inclusive and just. If we wish to create equitable outcomes, power sharing with communities can assist. Valuing and supporting the community sector is another way to transfer power back to communities. This is explored in the next two chapters.

Value of community organisations

Community organisations are fundamental to society, however they are not acknowledged as such in our economic models. An attendee highlighted that the current economic model is not serving the community sector well. An attendee at the focus group stated “the community sector is often treated as the second class sector”. Furthermore, the value of the community sector is not fully recognised. A focus group attendee stated, “the NGO sector is not valued”. Although, the community sector does receive some resources and funding from the public and private sectors, the three sectors are out of balance. Rebalancing the three sectors was the subject of a recent book title ‘The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind’ by Raghuram Rajan. This book argued that strengthening and empowering local communities was an antidote to growing despair and unrest. Under this approach, our economic models would recognise the value of the community sector.

In regards to climate change, an attendee at the focus group explained that climate change is a global issue, but that solutions happen on the ground with communities. Another attendee stated that “communities can solve their own problems”, another said “ask the community, they are best placed to solve their problems”. This was highlighted at the focus groups; numerous community organisations that are passionately working to solve environmental and social issues. Numerous examples of community-led change were mentioned at the focus groups. This included community gardens, urban farming, community energy, etc. The value of community organisations goes beyond the tangible impact, community organisations further build community. An attendee said, “taking action at a local level gives you sense of belonging. Communities of place becomes communities of interest, becomes a story of making change across the country.”

Another way of looking at the value of the community sector is through the Four Wellbeing lens. Furthermore, the community sector creates cultural, social, environmental and economic value (and therefore wellbeing). Therefore, the community sector assists the local government to fulfil its purpose. Furthermore, the Local Government (Community Well-being) Amendment Act 2019, brought the four aspects of community wellbeing; cultural, social, environmental and economic, back into the Local Government Act 2002. Despite community organisations being invaluable in the community, some attendees felt that local councils had no trust in the community. One attendee stated “councils are not taking community groups seriously”. But it is not just local councils not taking community groups seriously, the imbalance between the private, public and community sectors suggests that it is not taking seriously more widely.

The value of the community sector was the topic of a UK report titled ‘Community Power: The Evidence’. These researchers asked, ‘what is the value of community power now?’ The report starts by explaining that two paradigms, the state paradigm and the market paradigm, have become dominant since the early 1900s. They propose that there is a need for a new model of public service delivery: the Community Paradigm. This involves communities taking back power to design and delivery services. The report provides an evidence base of the impact of community power to support their proposal. Firstly, the report explains that “the term community power captures a wide range of different practices, approaches and initiatives. Common to all of these is the principle that communities have knowledge, skills and assets which mean they themselves are well placed to identify and respond to any challenges that they face, and to thrive.” The report highlights that:

- Community power can improve individual health and wellbeing

- Community power can strengthen community wellbeing and resilience

- Community power can enhance democratic participation and boost trust

- Community power can build community cohesion

- Community power can embed prevention and early intervention in public services

- Community power can generate financial savings.

These impacts that community organisations can create are important for climate action. In the words of the Community Power report, ‘unlocking community power and shifting to a community paradigm’ is important for combatting the climate and ecological breakdown. The next chapter explores some ways that this can be achieved.

Realising community organisations' potential

At the focus groups, we repeatedly heard that communities aren’t given the funding, resources or trust they need. Furthermore, although communities can solve their own problems (as discussed in the previous chapter), they “struggle with the resources to do the job properly” according to a focus group attendee. The barriers to successful community-level change are well understood. A New Zealand report found that “the achievement of desired community outcomes is hindered by a number of factors, including:

- Adverse funding and accountability arrangements

- A central-government culture that is not well-aligned with working with communities

- An unsupportive policy and regulatory environment” (Ball, 2015).

These barriers were discussed at the focus groups. Dealing first with underfunding and under resourcing, an attendee argued that there is a lack of investment in communities, and another explained that community organisations are underfunded. Another stated that it is difficult to secure funding for long-term functionality of community organisations. This means that it is difficult to get the resources needed to build partnerships as well as capacity and capability. Resources go beyond money; an attendee commented communities do not have access to land and other resources. The slim funding and resource base creates competitions, and may result in the community sector needing to fight for the funds. Underfunding and under resourcing limits the community sector. Secondly, trust. Some of the attendees commented that a lack of trust also limits the community sector. An attendee stated that there is “not a lot of trust for community initiatives”; another said that “funding comes with red tape”. We heard that there are regulatory constraints and bureaucratic mechanisms which shows that funding is based on rules and transactional relationships rather than trust based partnerships. Another attendee explained that funding can come with pre-set criteria, outcomes and objectives that don’t necessarily reflect the community. This is problematic and limits community-led change.

Solutions for realising the potential of the community sector were also discussed at the focus groups. Attendees called for long-term and sufficient funding, this includes resourcing capacity building. One attendee commented on the need for community organisations to be valued in our economic models. Another attendee explained that there are many demands on iwi and whānau, which require funding. Indigenous procurement was also discussed as an solution. Another attendee expressed that communities should be enabled to use land. Solutions relating to trust include sharing power so communities can implement their own solutions, removing regulatory constraints and barriers, and creating trust-based partnerships.

The UK report, Community Power: The Evidence, which was discussed in the previous chapter outlined four shifts and recommendations for realising the potential of community power. These were:

- Practitioners should collaborate to share learning and build a stronger evidence-led case for the impact of community power approaches

- There needs to be an ambitious approach to devolved, place-based budgets across local public services, as a core prerequisite for transferring more power to communities

- The Treasury should adopt a wellbeing approach to budgeting

- Parliament should pass a Community Power Act. The Act would have four goals: to enshrine community rights; to enable community-focused devolution; to establish a Community Wealth Fund; and to provide a permissive legislative and regulatory framework for community power.

Parliament should pass a Community Power Act. The Act would have four goals: to enshrine community rights; to enable community-focused devolution; to establish a Community Wealth Fund; and to provide a permissive legislative and regulatory framework for community power.

The New Zealand report mentioned above also looked at how central government could best support community-level initiatives. It presented the following solutions:

- Remove bureaucratic barriers

- Collaborate

- Enhance capacity at both community and government levels

- Invest strategically

- Create a supportive policy context (Ball, 2015).

Communities are already contributing to a low-emission, regenerative, distributive and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand; realising community organisations’ potential can further help Aotearoa New Zealand combat climate and ecological breakdown. This can be done by greater funding, resources and trust for the community sector. It also involves valuing the community sector within our economic models and transferring more power to communities so that these communities can continue to create systems change.

Abson, D., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C., Jager, N., Lang, D. (2016). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. AMBIO A Journal of the Human Environment.

Ball, J., & Thornley, L. (2015). Effective community-level change: What makes community-level initiatives effective and how can central government best support them?.

Birney, A. (2015). How might people and organisations, who seek a sustainable future, cultivate systemic change? Lancaster University.

Geels, F. (2019). Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: a review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 39. 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.06.009.

Meadows D (2010) Thinking in systems a primer. Earthscan.

Rotmans, J., Kemp, R., & Asselt, M. (2001). More Evolution Than Revolution: Transition Management in Public Policy. Foresight. 3. 15-31. 10.1108/14636680110803003.