Regenerative, distributive, resilient Aotearoa

Introduction

As part of BERL’s pro-bono mahi, we are undertaking a green pro bono study. We have approached this study by considering what a low-emission, regenerative, distributive and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand looks like for communities. This article (which can alternatively be read as a discussion document) provides a starting point for kōrero about our study. It lays out BERL’s perspective of the economy and its role in achieving a low-emission, regenerative, distributive and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand. The key premise of this article is that a wider economic model that values our people and our planet is valid and necessary. Not only is it valid and necessary, it is fundamental if Aotearoa New Zealand is to overcome our twenty-first century challenges.

Aotearoa New Zealand is unique for many reasons, it is important that this informs the foundation of our approach to combating climate and ecological breakdown.

Where’ve we come from?

Our key historical events as stated in the BERL Whano report are:

- Circa 800: Polynesian explorers, the ancestors of present-day Māori, began to arrive in successive waka migrations

- 1779-1820: Contact with European settlers

- 1840: Te Tiriti o Waitangi signed between the British Crown and some Māori Rangatira

- 1840- 1930: The New Zealand Wars. Land confiscation and sales reduced land occupied and controlled by Māori to five percent

- 1975: Waitangi Tribunal established to investigate breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

- 1985: Waitangi Tribunal empowered to investigate Treaty claims dating back to 1840, which opened significant new avenues for redress

- 1990s: Iwi settlements for historical redress begin.

The Whano report highlights that these key events, and other consequences of colonisation, have had long lasting and severe effects. Historic and ongoing systemic and structural racism have perpetuated inequality, and climate and ecological breakdown. Failing to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi is central to this structural racism. Table 1 outlines the differences in meaning between The Treaty of Waitangi and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Honouring Te Tiriti so that Māori have sovereignty must be the foundation from which Aotearoa New Zealand combats climate and ecological breakdown.

| The Treaty: Differences in meaning | ||

|---|---|---|

| English version | Te reo Māori version | |

| Article one | The Māori chiefs agree to give the Queen of England sovereignty over New Zealand | The chiefs agree to give the Queen of England kāwanatanga over New Zealand |

| Article two | The Queen promises that Māori will always have possession of their land, forests, and fishing grounds | The chiefs are promised tino rangatiratanga (total chieftainship) over their whenua (land), kāinga (villages), and taonga (treasures) |

| Article three | The Queen gives the people of New Zealand her royal protection and all the rights and privileges of British subjects | The Queen gives the people of New Zealand her royal protection and all the rights and privileges of British subjects |

An economic perspective on where've we come from

The post-WWII economic ‘consensus’ agreed a moderately active role for governments in the management and regulation of economic activity. The rules for cross-border trade and payments were founded on the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, with International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank institutions providing further institutional frameworks. Governments were, by and large, active in what were called ‘non-market’ sectors (e.g. health, education, and transport infrastructures). There was acceptance of the provision of collectively-provided safety nets, or supports, for unemployed and others unable to work. The economic recovery from the devastation of WWII enabled employment and incomes to generally grow through the 1950s and 1960s. Additionally, improved health services and education opportunities were increasingly available. However, for various reasons, the 1970s were an unstable economic era; increased unemployment along with government debt and deficit concerns accentuated the unstable situation.

The mid-to-late 1970s saw a sea-change across mainstream economic thinking take hold. The prescription surged towards favouring a more market-oriented approach to economic management and regulation. Critically, governments were severely criticised for their interventionist approaches and their hampering of the mechanism of the markets. This sea-change in thinking was given a huge boost with the elections of Prime Minister Thatcher in the United Kingdom (in 1979) and President Reagan in the United States (in 1980).

This was the start of the era of small government, low taxes, and reduced regulation. This era promised prosperity for all in the sense that those who participated in market transactions received beneficial returns commensurate with their effort (adjusted for the risk of the activity). Hence, those employed would receive a wage consistent with the market value of their labour’s share of the goods or services produced by their labour. Similarly, the owners of capital (land, buildings, machinery, and equipment) would receive profit consistent with the market value of their capital’s share of the goods or services produced by their capital.

Government activity and involvement was to be restricted to taxes required to enforce the rules of the market and the laws of society, along with defence of the realm. Government safety nets were to be minimised to that necessary to avoid abject poverty, but needed to be insufficient so as not to interfere in the incentive to participate in the market (i.e. offer your labour).

Further, in terms of overall management of the economy, the government was not to be trusted with control over the issuing of currency and credit. In direct response to the inflation experience of the 1970s, which were deemed the result of insufficient government control of the money supply, the control over the issuing of currency and credit was officially contracted-out to central banks. They were to operate under a devolved mandate that targeted stability in the level of prices, either through manipulation of interest rates, or the control of credit.

The use of fiscal policy (i.e. changes in government taxes and/or spending) to manage inflation, unemployment, or other aspects of the economic cycle was actively discouraged. This discouragement was through a combination of explicit legislation, political pressure and influence from international institutions like the IMF, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank.

The breakdown of the Bretton Woods agreement eventually led to a range of floating exchange rate mechanisms for most major currencies. Alongside this change was a move to much freer financial capital movements across international borders. Global financial integration assisted in financial capital moving to areas with better (risk-adjusted) returns, with interest rate and share price movements across borders inevitably becoming similarly integrated.

In a similar vein, global trade barriers were relaxed across a range of goods. Multi-lateral trade groupings and agreements were advanced and the role of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) became increasingly prominent. This assisted in the development of globally integrated supply chains. The past 30 years have seen a large increase in global integration, as supply chains, financial capital, people, and technological advances have been shared across all corners of the world. Relative and absolute reductions in numbers in abject poverty have resulted in many parts of the world.

Despite these advances, disparities between the privileged and the poor have become entrenched and, in places, have widened.

The model of globally integrated business – with reduced government regulation – assisted the development of a ‘race to the bottom’ in terms of conditions of employment, wages, and addressing external costs. The accumulation of market power by large cross-border enterprises acted against the ability of governments to impose minimum criteria (for example, employment or environmental regulations). The ‘race to the bottom’ is reflected in increasing numbers in minimum wage employment, reduced allowances for leave, as well as increasing casual and contract work arrangements.

In terms of external costs, environmental degradation has accelerated, despite numerous attempts to impose environmental charges, or taxes, or regulations. International agreements continue to be hindered by domestic political agendas, which can be relatively easily manipulated by enterprises, sectors, and industries wishing to protect their status quo.

Central bank management of economic cycles did indeed control price inflation of consumer goods and services, but assisted (directly and/or indirectly) in the inflation of asset (land, housing, property, shares) prices. This provided gains to those with existing wealth (in terms of increasing the financial value of that wealth). Conversely, those with minimal or no existing wealth were faced with increasing difficulty in attempts to acquire wealth.

The depths and regularity of recurring global crises has undermined the argument that the market mechanism is inherently self-correcting. Further, the origin of these crises being the financial markets illustrated the weaknesses and vulnerability of minimally regulated globally integrated financial capital markets. Ironically, in times of crisis the expectation for government to intervene is uncritically accepted by market proponents. However, the response of governments to these crises has appeared to disproportionately favour those with existing financial assets. Those engaged in economic activity (including those employed in the production of goods and services) have been left with the impression they are further back in the queue. This impression has been reinforced in the post-GFC era, with a stagnation in real wages for those employed (and actual reductions in several countries) compared to a large and prolonged boom in asset prices (in particular, house and share prices) over the last decade.

This perceived manipulation of the ‘rules of the game’ in favour of large cross-border enterprises, or groups with existing wealth and power, has further alienated communities who increasingly see little to gain in playing ‘by the rules’.

Where are we?

We were promised prosperity for all, but what did we get? New Zealand, like the globe, sits on several burning platforms. Depending on one’s perspectives, there are many pressing issues that threaten our way of life and our traditional models of analysis. From an economics perspective, some are depicted in Figure 1.

From an economic perspective, the pressing challenges facing Aotearoa New Zealand can be grouped as:

- Inequality of opportunity that risks increasingly disconnected and disenfranchised communities

- A fragile environment depleted through activity focused on extraction and exploitation of natural resources

- A market model of jobs and incomes that is unable to sustain household, family, and whānau.

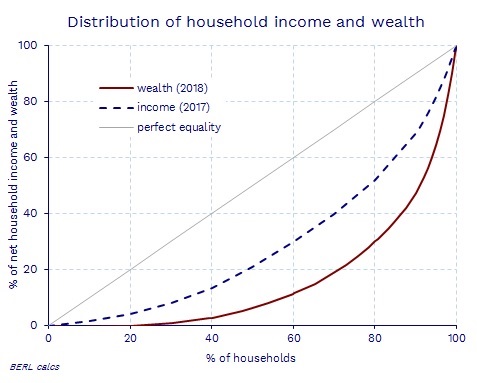

Inequality

Figure 2 shows that, using latest available (2017) data, the distribution of household income sees 50 percent of New Zealand’s households receiving only 20 percent of the nation’s total household income. Figures for 2018 indicate 50 percent of households possess approximately 10 percent of the nation’s total household financial wealth. Conversely, 50 percent of households possess close to 90 percent. Of considerable concern is the first 20 percent of households that are effectively ‘under water’ on this chart. With less than zero financial wealth these households will be living in rental properties, have no opportunity to enter into business, will have difficulty funding future training or education for their younger generation, may well be in significant debt to high-cost lenders (commonly known as loan sharks), and for which savings (whether for emergencies or for old age like KiwiSaver) will be a dream. This applies, more or less, to one in five households across New Zealand.

Source: Statistics New Zealand, BERL

Extracted and exploited environment

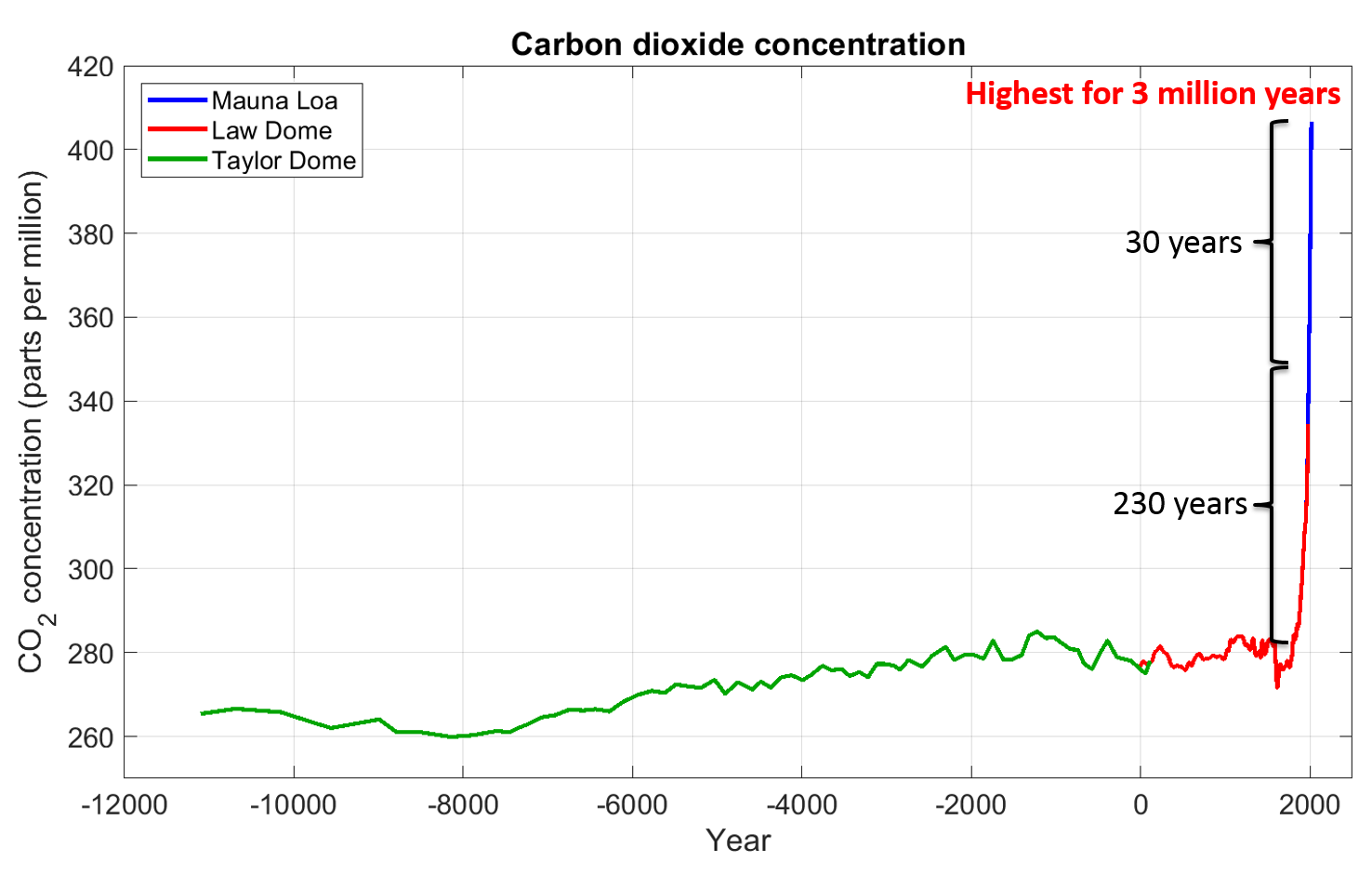

Despite the climate change challenge having been with us for three (if not more) decades now, it has become even more pressing given an increasing number of extreme climate events around the globe. Climate, ecosystems and communities are fundamentally interconnected. Not only does the climate and ecological breakdown impact upon communities (impacts and adaptation), communities’ impact upon the climate and ecosystems (mitigation).

Figure 3 shows how humans are causing climate change at a rapid speed.

Climate change can be framed in various ways. From an economic perspective there are many factors contributing to or influencing climate change. One example is our economic model. Economists often debate over whether production or consumption drives the economy, but both approaches are rooted in consumerism. It is unlikely that greenhouse gas emissions will reduce through this model.

Another example is how we define economics. Many economists define economics as the allocation of scarce resources. Arguably, it is a definition like this that has gotten us into this climate and ecological mess. Our environment is not a stock of assets to be extracted and exploited, it is a treasure to be enhanced and protected.

Our current narrow economic approach has contributed to the climate and ecological breakdown.

Increasingly precarious jobs and incomes

The disparity between employed income and those reliant on the social security safety net has widened in recent years. In such a context, the presence of one’s own safety net (i.e. savings) alongside the community’s social security safety net becomes critically important. For those that have had little opportunity to build their own safety net (for example, the young and/or those who have inherited little), the community’s social security net is the only backstop.

The stigma associated with being a beneficiary is debilitating for many, which is reinforced by restrictive conditions, barriers to obstacles and delays to receiving assistance. This can work to undermine any sense of respect an individual may have and, rather, fosters exclusion from activities and community. This market model of jobs and incomes is unable to sustain households, family and whānau.

Where are we going?

Since the onset of COVID-19, there have been many people re-imagining Aotearoa New Zealand. The surrounding kōrero is about how we can combat the many challenges we face: climate and ecological breakdown, inequality, systemic racism, housing unaffordability etc.

Currently, Aotearoa New Zealand does not have a strategic plan, meaning that we are blindly navigating the challenges of the twenty-first century. In terms of climate change, Aotearoa New Zealand does not have a coherent and comprehensive guiding framework, instead there are a collection of initiatives throughout government, private sector, non-governmental organisations etc. But the parts are not summing up. This will need to be addressed to enable us to combat climate and ecological breakdown.

What is the economy?

Often, the needs of ‘the economy’ is used by some to take a weaker stance on climate action. Businesses, industries, and government have hid under the guise of ‘climate action hinders the economy’ to prevent action. This begs the question, what is “the economy”. Is it machine or beast? Is it mechanical or animal? Is it domesticated or does it range wild? And, where did it come from?

GDP growth gone mad

In general, the narrative surrounding the economy takes a business or financial perspective. When people ask, how is our economy? They want to know, what is our current GDP growth rate? Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is used to measure a country’s economy. GDP growth was originally used as a means to an end, a way to achieve our goals. However, GDP growth has become the goal. We have become so attached to inputs and outputs that we forgot about the outcomes.

This is a narrow approach. New Zealand in recent years has attempted to take a wider approach. However, for a number of reasons, difficulties prevail. One reason is that it is difficult to collect the required data. Often the available data represents the ‘productive’ or paid economy. Another reason is that a quantitative data analysis approach is taken for measuring the economy. This approach often provides a single numeric value for the economy, and the numeric value is often a monetary value. But measuring economies through a narrow framework lens fails to represent the full picture of the economy. GDP is a single numeric, it cannot reveal the quality of a countries economy.

The good news is that this perspective of the economy is a social construct, informed by context. Social construct can be changed, and should be changed to reflect its societal context. Our economic model is outdated, and as such we should update it to reflect the twenty-first century.

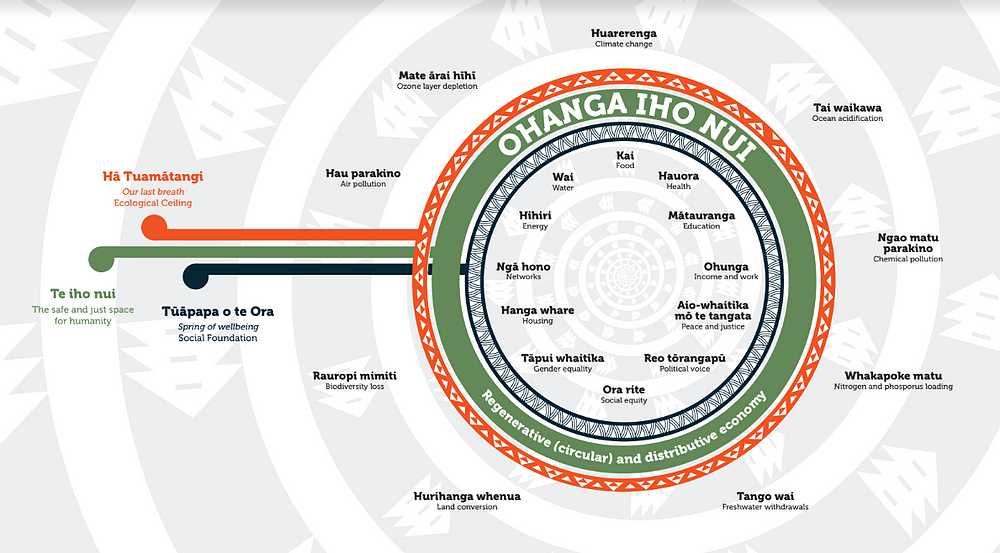

People and planet

A broader economic perspective would deliver wellbeing. A wellbeing–based economy would value our people and our planet. Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, has done extensive work around a people and planet economic model. The model is about moving away from endless GDP growth as an economic goal, to an economy that values and provides for people and the planet. This involves designing the economy to be distributive and regenerative. The next chapter outlines what this new economic model could look like.

Furthermore, Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach should recognise the interconnectedness of people, the planet, and the systems that govern our lives.

A ‘just’ transition

The Government has signalled that it will prioritise a just transition, however it is unclear what is meant by a just transition, or who the just transition is for. The National Climate Change Risk Assessment for Aotearoa New Zealand found that climate change will exacerbate existing inequalities and create new and additional inequities, due to differential distribution of climate change impacts. It is important that the just transition is for those who bear the burden of inequality, rather than those attempting to retain the status quo.

As such, involvement of all communities must be a guiding principle for Aotearoa New Zealand as we combat climate and ecological breakdown.

A new economic model

Wider economic models have been developed; below is an example of an alternative economic model specific to Aotearoa New Zealand.

Te ao Māori doughnut model

Figure 4 shows the doughnut model reimagined from a Tūhoe Māori perspective, with the environment as its foundation, and social elements on the outer ring.

Interconnected models

Economic narratives fed into various systems that govern our lives.

Business model

‘Clever business’ is still written in terms of dollar value, rather than wider social and environmental value. However, there has been a shift towards social enterprises and other entities that deliver wider and intergenerational value. The new economic model would encourage markets, businesses, other entities, industries etc. to solve the problems of the twenty-first century by supporting people and the planet. This will likely result in better outcomes for people and planet.

Policy model

Policy is conducted within an economic framework, however a narrow economic model is currently applied. To achieve wellbeing as an economic outcome, wider economics must be applied to policy. The new economic model would encourage a wider perspective on economics, and would prevent the ‘economy’ being a reason to forego climate action. This will likely result in better outcomes flowing from policy.

Funding model

The funding model in Aotearoa New Zealand takes a narrow and short-term approach. The new economic model would encourage an intergenerational approach to funding that focuses on long-term outcomes rather than short-term box ticking. The model would also reflect the value of funding communities, and as such it would encourage funding communities. This re-imaging of value would also encourage green procurement throughout supply chains which will support sustainable businesses.

Community power

There is a network of communities that are already contributing to a low-emission, regenerative, distributive and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand. This chapter highlights a few examples to help paint a picture of what Aotearoa New Zealand may look like in the future if we have transitioned towards such a vision.

The examples are broken into energy, food, and circular systems to align with our initial research. This research can found on our website:

Energy

Blueskin Energy Network (BEN) is a community based electricity retailer. BEN works within local networks to increase community resilience, reduce power poverty and support clean renewables. It began by enabling the community to share renewable energy generated by households. BEN demonstrates the possibility of small scale renewable energy generation in communities. This is a great example of climate action in communities as it positively impacts upon people and the planet. The technology is available for peer-to-peer trading of renewable electricity, but widespread dissemination is restrained by the focus on competition in the electricity market rather than service delivering flexibility and community value. Increasing access to community energy offers a great solution for transitioning towards a low-emission economy.

Food

There are numerous examples of New Zealand farmers shifting towards agricultural practices that support a healthy planet. One example is PermaDynamics. PermaDynamics is an organic permaculture farm on community trust land in Matapōuri, Northland. The Lotz family have created a farm that has a diversity of agro-ecosystems for food, community and climate resilience. The farm strives to enrich soil fertility, sequester carbon, enhance wildlife and provide a model for regenerative living. The food forest has over 250 plant species which creates a sanctuary and breeding zones for native birds. The food forest and garden also provides the community with nutrient dense, organic food. This form of food production also helps regenerate and build healthy soil.

Circular systems

Circular systems require changes throughout all supply chains and systems that are used for production and distribution of goods and services. We need to re-imagine how we design, manufacture, package, warehouse, transport, and market goods and services. It’s therefore more difficult for communities to implement without systems change. None the less, there are examples of communities implementing circular systems, such as the Para Kore programme. This programme works with marae to increase the reuse, recycling and composting of materials to reduce the extraction of natural resources and raw materials from Papatūānuku.

These examples illustrate exciting opportunities for future developments for Aotearoa. Our challenge is to devise next steps to learn and build from these examples.

Next steps

This article provides a starting point for kōrero. It lays out our perspective of the economy and its role in achieving a low-emission, regenerative, distributive and resilient Aotearoa New Zealand. The key premise of this article is that a wider perspective on economics is valid and necessary, and that a redesigned economic model is fundamental if Aotearoa New Zealand is to overcome our twenty-first century challenges.

In undertaking this study, we hope to support, or contribute to, the abundance of work being done in the climate and ecological breakdown space. To us, this means engaging with others, encouraging participation in this kōrero from varying perspectives, sharing knowledge, and learning from each other to work towards our shared objective of a healthy planet. As such, we invite discussions about this project or climate and ecological breakdown more generally.

To inspire discussion, we have included a list of questions below:

- Does the low-emission lifestyle involve regenerative and distributed agriculture, renewable and decentralised energy, and the circular economy?

- What are the challenges to implementing these within communities?

- How can these barriers be overcome/what are the potential solutions?

- Who should be involved in overcoming the barriers/who are the enablers?

- What are other community solutions?

- How can we support community climate action?

- What are the challenges to community climate action?

- How can these challenges be overcome?

- Who should be involved in overcoming these challenges?

- Do you agree that a wider economic model is required?

- What other changes to the systems that govern our lives are required to support communities?

- How can we incentivise climate action?

These questions are a starting point, we welcome discussions more generally. But we do wish to keep the focus at a community level. For completeness, we have adopted the following description of communities from our BERL Engaged communities report.

- Communities of place – a community of people who live within the same geographical boundary

- Communities of interest – a community of people who share a common interest

- Communities of identity – a community of people who share common affiliations or experiences.

Please email Hannah Riley at [email protected] if you are interested in discussing further.