The phrase “demography is destiny” attributed to French philosopher Auguste Comte, may be an exaggeration, but it helps to highlight why understanding demographic shifts is crucial to the study of the economy.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, our high rate of migration and ageing population are two demographic factors that are already, and will continue, shaping the labour market.

Why is the population ageing?

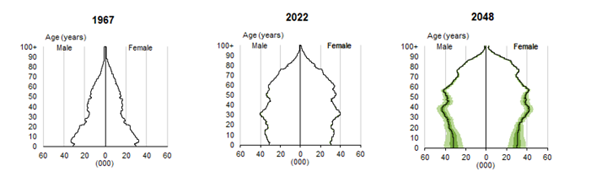

Fertility rates are falling the world over. Aotearoa New Zealand’s current fertility rate of 1.6 births per woman is half the rate of 1970 (3.2), and significantly lower than the replacement rate of 2.1. This decline is a result of a complex mix of social, cultural, economic, and personal factors. Not only are fewer babies being born, but people are also living much longer. The average Kiwi could expect to live to the age of 70 in 1970. Today, the life expectancy is 82.8 years. These two trends in combination will inevitably result in an inversion of the population pyramid.

Source: Statistics New Zealand

Migration is keeping our population young, for now.

In 1970, the median age for a New Zealander was 26 years. By 2013, this had increased to 38 years. Since then, annual net migration inflows have kept the threat of a rapidly ageing population at bay. Young people from all across the globe have moved to Aotearoa New Zealand in search of new economic opportunities. We rely heavily on labour from countries with a surplus of young people, and migration has been largely driven by 18-to-39 year-olds. Over a quarter of our population is made up of migrants, one of the highest rates in the OECD. These young migrants add immense value to our economy and society in a myriad of ways, not the least of which is by supporting our older population. Research by the New Zealand Aged Care Association has shown that about 40 percent of caregivers are migrants on various types of visas.

The median age is expected to surpass 40 years in the 2030s, and by 2073, half the population is expected to be older than 45 years. In a world without migration, there would be a much faster acceleration: the median age would jump to 50 years by 2073, and a third of our population would be over the age of 65 years, compared to a quarter with high migration.

Why does it matter?

The socio-economic implications will be important. Some are already visible through the experiences of countries like Japan, but many will only become known over the next few decades. From a social perspective, young people may face a higher burden of care within their families, loneliness and isolation amongst older people could increase, and the well-being and quality of life for older people may decline.

The economic consequences will also be hefty. A rapidly ageing population equates to an equally rapid increase in an ageing, and shrinking, workforce. The number of people aged between 15 and 44 years in the labour force is already on the decline and is expected to shrink by over seven percentage points by 2073. This will result in an increasingly older workforce as the percentage of older workers grows.

With fewer young people to care for them, older people may have to continue to work for longer to ensure that they are able to live a life of dignity and comfort. At 25 percent, Aotearoa New Zealand already has one of the highest rates of over-65s in work, compared to 10 percent for the UK, 12 percent for Australia, and 20 percent for Japan. As the fiscal burden on the state of providing care and superannuation grows, the age of eligibility for superannuation will not be sustainable at current levels. There are plenty of advanced countries that are already beginning to increase the age of eligibility.

Discussions around the future of work for older people must look at easing current challenges, which will impact a growing share of the workforce over the years. For instance, older workers are more prone to displacement during economic shocks; they have trouble accessing training and education opportunities; and they struggle to change jobs or re-enter the workforce. The outcomes are even worse for certain groups of older workers. Māori, Pacific People, women, and disabled workers aged over 50, have higher rates of unemployment and underutilisation compared to their counterparts.

The impact on young people must also not be ignored. The social contract where the young support the old may not be sustainable anymore. The 65+ dependency ratio is expected to double from the current 24:100 people to 50:100 people by 2070. This will impact young people’s labour market choices. In the UK, the overall value of unpaid care work is increasingly driven by adults requiring full-time care. Those with higher caring responsibilities are less likely to participate in the labour market at the same rate as others.

Preparing for an ageing workforce will require a sea change at all levels – regulatory, organisational, community, and societal. There will be big hurdles to cross, such as ageism, the lack of flexible work options in all industries, and the ability and readiness of the ageing population to upskill. The use of technologies, such as automation, robotics, and AI, opens a whole range of new possibilities and support mechanisms. It will also be important for policy to ensure intergenerational equity as the fiscal burden on young people grows.